Bees are as complicated as they are amazing. They are an autonomous, synergistic society called a superorganism, guided by biological directives and instinct. Without these hard-working creatures, cross-pollination wouldn’t be possible, and the earth’s vegetation will start to deteriorate. To understand the predictability and intelligence of bees, we need to look at their anatomy.

The body parts of a bee include;

- The Head

- Mouth

- Eyes

- Antennae & Their Sense Organs

- The Thorax

- Cuticle (Exoskeleton)

- Wings

- Legs

- The Abdomen

- Stinger

- Glands

- Circulatory System

- Digestive System

- Nervous System

- Respiratory System

- Reproductive System (Male & Female)

If you are curious about the bee’s anatomy, this article provides all your information. We will discuss every part of the bee and share some interesting facts about one of the most productive creatures on the planet.

The Anatomy Of The Bee – Body Parts Of A Bee

A Bee’s body is divided into 3 segments; the head, thorax, and abdomen. Each section has complex systems that contribute to the bee’s overall performance. Let’s take a detailed look at each section below;

1. The Head

The head consists of multiple parts; the mouth, eyes, and antennae.

The Mouth (Mandibles, Proboscis, & Epipharynx)

Honey bees have multiple mouthparts. They use a hinge-like, horizontally-orientated outer section of their mouth called mandibles to work with wax, bite, tear, groom, grab food, and stabilize and guide the proboscis.

The proboscis is a retractable, sucking, inner mouthpart with multiple tubes to sense taste and drink nectar, water, and honey. When the proboscis is not used, it folds and tucks into a small groove beneath the bee’s head. The Epipharynx is a median lobe underneath a hairy tongue-like labellum that is grooved and elongated to form a tube for sucking when apposed.

The Eyes

A bee’s vision is different from our vision. Humans can see all the visible light in the color spectrum, whereas bees can see past spectrum colors into the ultra-violet spectrum, allowing them to see colors that we cannot see.

They have three small eyes located at the top of their head used to see the light, and two compound eyes used to see shapes. Flowers have evolved so that their petals have ultra-violet patterns that attract bees and increase the possibility of pollination.

The Antennae & Their Sense Organs

A bee uses its two flexible appendages (antennae) and sense organs for smelling and feeling. The segmented antennae are attached in ball and socket joints to the center of the bee’s head.

The antennae consist of different sections; the first part is called the scape, and the second part is the pedicel (a hinge-like joint that allows the antennae to bend at almost 90 degrees). Lastly, the terminates are located in the segmented flagellum.

Female bees have eleven segments in their flagellum, whereas drones (male bees) have twelve. Extremely sensitive receptors cover the antennae allowing the bees to register various information such as humidity, vibration, touch, temperature, and scent.

Bees register vibration and sound through their Johnson’s organ (a collection of sensory cells in the pedicel). Each antenna has over 5000 olfactory receptors making its sense of smell 50 times stronger than a dog. Sensory information is transmitted by a large nerve located in a straw-like tube in each antenna.

2. The Thorax

The thorax of bees consists of three parts: the cuticle, wings, and the legs.

The Cuticle

A bee has an exoskeleton (an outer skeleton) called a cuticle and is made of chitin, a waterproof, highly-durable substance composed of tergites on top and sternites underneath. These plates expand and contract as the bee moves with the help of flexible membranes. Interestingly, not all bees have the same cuticle.

Depending on their location, a bee’s cuticle varies from scale-like to smooth and houses their internal organs, protects them from environmental elements, acts as a frame to which their muscles are attached, and anchors its hairs that collect pollen.

As a bee increases in size, bees molt 6 times in the larval and pupal stages of their development, and when adult bees emerge from their capped cells, they retain the cuticle they were born with until they die.

The Wings

The two pairs of bee wings are anchored to its upper thorax and carpeted in tiny spines. Its hind wings lay under the fore when at rest, and the upper edge of the bee’s hind wing locks into the hind edge of the fore with the help of humuli (microscopic hooks).

The surface of their wings is made of chitin (like the cuticle) and is enclosed by veins, margins, and cross veins where the bee’s blood (hemolymph) flows. Though it seems like bees are flying back and forth, they are actually just twisting and moving their wings in a figure-eight pattern.

They are too heavy for their wings, and this motion helps them to stay in the air. Compared to a hummingbird’s 70 movements per second and a dragonfly’s 30 moves per second, a bee can move its wings an incredible 300 times per second. The bee’s indirect flight muscles create metabolic friction to generate heat by moving isometrically.

They also have smaller muscles that control subtle movements, which allows the bee to control their flight efficiency and precision. Abundant trachea supplies high oxygen levels to these flight muscles, fueling the metabolic flying demands.

A bee also utilizes its wings for direct ventilation, which is necessary to cool the hive’s internal temperature during very hot seasons, which can become deadly. Honey bees spread water drops throughout the hive and fan them with their wings to create a cooler environment.

Have you ever seen bees lined up in a single file at the hive entrance with their heads down and their rear ends in the air? This is when they expose the Nasonov gland and use their wings to fan wind over it and disperse volatile pheromones.

The Legs

A bee has six multi-jointed legs, and each leg has six segments (from hip to toe); coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, tarsus, and pretarsus. Their front legs clean the pollen from their bodies and antennae with comb-like hairs.

When worker bees collect pollen, they store it in a pollen basket located on their hind legs. These baskets have spikes that hold the pollen in place. Each pair of the bee’s legs has appendages to perform various tasks.

- The Front Pair of Legs – between the tarsus and tibia located in the joint, is a squeegee-like, notched structure that the bee uses to clean its antennae. The bee also uses its front legs to transfer pollen to its hind legs.

- The Middle Pair of Legs – Each middle leg has a spur located at the end of the tibia used to manipulate wax flakes and might also be vestigial. The bee also uses its middle legs (with its front legs to transport pollen to its hind legs.

- The Back Pair of Legs – An apparatus called a rostellum, made of tiny rakes, scrapes the pollen and deposits it on a ledge called an auricle. The joint between the tarsus and tibia presses the pollen when the bee bends and pushes it into a concave surface located on the outer tibia, held in place at the corbicula (pollen baskets) by long curved hairs.

Even though bees have 6 legs, they walk in a tripod-style and only use three legs for each step (they alternate touching the surface; the front and back on the left with the middle leg on the right, or the front and back legs on the right with the middle leg on the left).

Each leg has a pretarsus at the distal end of each leg. It consists of long and short claws called ungues. An organ called an arolium (soft extendable pad) covered in minute hairs that act like suction cups is located between the ungues and allows bees to walk on vertical surfaces.

The Arnhart gland produces a secretion known as footprint odor, which is located at the bottom part of the pretarsus from where the scent is released.

3. The Abdomen

A bee’s abdomen is made up of the stinger and various glands.

The Stinger

The honey bee (only the queen and the worker bee) has a 3-part stinger attached to a venom sac. The queen has a smooth stinger that allows her to sting many times, whereas the worker bee has a barbed stinger that detaches from the venom sac and abdomen.

The Glands

Bees have various glands. Glands are necessary to synthesize and secrete chemical compounds such as pheromones. Some of these compounds, such as hormones, are used within the body, some produce substances used by bees, such as wax, and the body secretes some like pheromones. Let’s look at each of the bee’s glands below;

Hypopharyngeal Glands

The hypopharyngeal glands are located in the bee’s crown and snake through its head and secrete into the worker bee’s mouth. These glands also produce worker and royal jelly during the first few weeks of the bee’s life.

As they age and transition from brood care to foraging, the glands produce a carbohydrate digesting enzyme, which splits the sucrose into fructose and glucose. Hypopharyngeal glands can also revert to synthesizing worker and royal jelly if necessary.

The Mandibular Glands

A worker honey bee has mandibular glands which are housed in its head. These glands exude 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid, 10-HAD, an antibacterial preservative that prevents deterioration of the latter if it is mixed with brood food (worker and royal jelly).

These glands also produce 2-Hepanone, which acts as a temporary immobilizer and alarm pheromone. This powerful pheromone is excreted when the bee bites hive pests like wax moth larvae. It also makes the other bees aware of the pest to remove these pests as a colony.

A queen’s mandibular glands produce QMP (Queen Mandibular Pheromone), serving various essential functions that serve colony cohesion. Drones also have mandibular glands that produce a powerful pheromone that establishes and maintains DCAs (Drone Congregation Areas).

The Paired Salivary Glands

These peculiar glands look like bunches of delicate grapes and are located in the bee’s head and abdomen. This oily substance produces sucrose to break down sugar, amylase to digest starches, and lipase to digest fat.

It also dilutes bee bread, lubricates the bee’s mouth, and softens wax. The glands connect in a common tube located in the bee’s head and empty this oily substance into the proboscis (on either side). The glands produce a pheromone that indicates brood presence in the larvae stage of the bee’s development.

Wax Glands

Worker bees have 4 pairs of wax glands in the abdomen’s last four sternites. Wax glands make liquid wax consisting of long-chain alcohols and esters of fatty acids. The bees exude this liquid onto smooth wax mirrors, where it hardens into flake-like sheets.

When the comb is damaged, a bee uses these sheets to repair it. These wax glands vary in productivity and size, and the most generative, largest wax glands occur on day twelve post-emergence.

The Nasanov Gland

Located below the intersegmental membrane of the sixth and seventh tergites is a gland called the Nasanov gland. Worker bees are the only bees with Nasanov glands, and they use them to produce a volatile pheromone to announce the location. When the worker bee extends and bends its abdomen during fanning, an upper part of this gland, resembling a ripe mango slice, is visible.

The Darfour’s Gland

Only female bees have Darfour’s glands (also known as alkaline glands) located below her oviduct. This gland empties into her vaginal wall, producing a pheromone that impedes the ovary development in worker bees. When the queen exudes this pheromone, it stimulates the worker bees to form circles of attendance (retinues) around her.

The Koschevnikov Gland (Sting Gland)

A tiny organ called koschevnikov (sting gland) is situated near the sting sheath. This gland is responsible for producing a volatile pheromone that gets released before, during, and after stinging.

The Tergal Glands

These glands produce a pheromone that evokes retinue behavior and are located underneath the posterior edges of the bee’s abdominal tergites.

The Arnhart/Tarsal Gland

The Arnhart/tarsal gland is located in the fifth tarsomere, the last section of each leg. It is made of a unicellular layer that surrounds a pouch-like reservoir. The footprint odor (an oily, colorless secretion) emanates through footpads (the arolia) as the bee walks around.

Many people refer to this as a trail pheromone because it is also released from the abdomen’s tip. Even though this gland secretion has a complex chemical composition, it is used to mark the area the bee has already visited.

Venom Glands

Only female bees possess venom glands that are located in their abdomen. These glands generate acid, which gets emptied into a venom sac and mixes with other chemicals to produce an inflammation and a pain-causing compound called apitoxin, released during stinging.

The Protothoracic Gland

The prothoracic gland is an endocrine, hormone-producing gland only found in larvae. It is a minute structure situated between ecdysone-producing thoracic segments, a steroid hormone that controls molting.

The Corpora Cardiaca & Corpora Allata Glands

These paired bulbous glands are connected and the brain and located in the bee’s head section, next to the esophagus. The corpora allata gland produces the juvenile hormone.

This hormone plays an indispensable role in the life of larvae, pupa, and grownup bees, whereas the corpora cardiaca glands’ function is unclear. JH regulates development through molting and growth in pupal and larval honey bees. In grownup bees, it controls role changes as the bees develop from their nursing duties to foraging.

4. The Circulatory System

Hemoglobin does not have to be present in a bee’s blood (hymolymph) to carry oxygen which means instead of being blue or red, their blood is colorless. It serves as a vehicle in which waste, nutrients, and chemical substances are transported and as a medium that distributes pressure.

A bee’s muscular elongated heart bumps blood and stretches from right behind the brain to the tip of the abdomen. The bee’s heart is divided into 4 chambers and 5 openings (ostia) pairs. The hymolymph is pushed from the abdomen into the thorax, which flows into the wings, legs, head, and brain.

After every cycle, the blood returns through open cavities in the body, where it collects new compounds and deposits waste, and starts a new cycle.

5. The Digestive System

A bee’s digestive system runs in a semi-straight line. Starting at the mouth, which is connected to the esophagus, extends all through the head and the thorax to the back of the abdomen. After a bee has consumed food, the food travels through the esophagus and into the honey stomach (crop), where it gets stored and transported back to the hive.

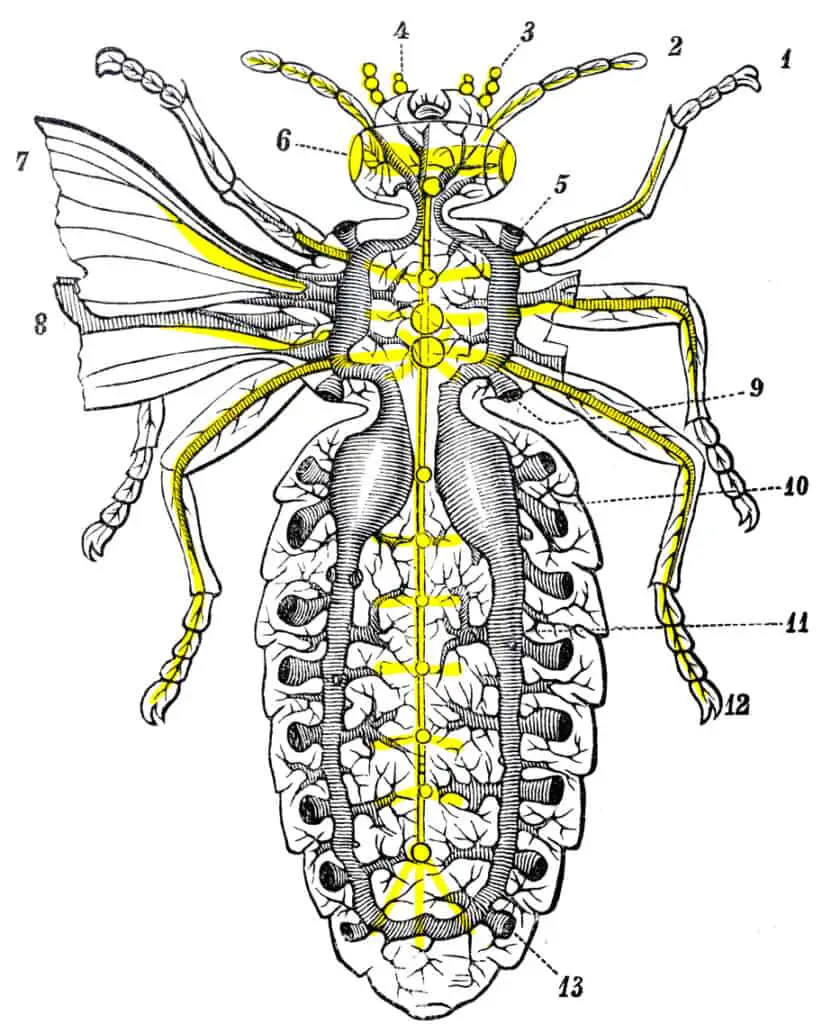

6. The Nervous System

The bee’s nervous system is extremely vital as it sustains, coordinates, and organizes the bee’s whole life. This system directs the bee’s actions and regulates behavior and perception allowing the bee to act as an interdependent and responsive colony member.

There are seven ganglia, of which five are located in the bee’s abdomen and two in the thorax (thoracic). Masses of information are gathered by an entire network of nerves (ganglia) distributed throughout the bee’s body.

Apart from the brain, the bee’s main locus of control, these segmented ganglia regulate semi-autonomous actions like sending and receiving information and leg movement. The oval-sized brain of a bee is made up of lobes connected by axons, has a volume of +/-1 cubic millimeter, consists of about 1 million neurons, and is the size of a sesame seed.

7. The Respiratory System

A bee breathes through 20 spiracles; 7 on each side of the thorax and 3 on each side of the abdomen. These are small openings compared to the atrium located right behind them. The atrium is linked to the trachea by an intervening valve.

The tracheal system branches into extremely fine tracheoles, and as it approaches, it penetrates and surrounds organs and tissue. When a bee rests, its abdomen pumps as it expands and contracts, pushing out expired gasses and pulling in clean, fresh air via the ostia.

8. The Reproductive System

The bee’s reproductive system is quite fascinating.

Female Bees

A truly amazing phenomenon about the worker is that even though their reproductive organs are latent, they can mature and start to function if the colony loses its queen. However, all their eggs are drones since they have never mated before.

The queen is much larger and has prodigious reproductive organs. Her eggs start in her ovaries as tiny cells and travel through ovarioles (egg tubules) to the oviduct. Here, the eggs grow larger as they descend and travel through the lateral oviduct into the common oviduct.

Here they will remain until they are either bathed in spermatozoa to become female or pass out unaltered through the vagina to become male. The spermatozoa are stored in the queen’s bulbous organ (the spermatheca), located in her abdomen.

This cache will fertilize her progeny for her entire life. Therefore, she keeps them healthy by producing nutritious secretions with her two spermathecal glands, and a network of trachea supplies their oxygen. The eggs (fertilized and unfertilized) move through the vagina’s valve fold and out the bursa copulatrix (the same organ that captures mucus and spermatozoa during mating.

Male Bees

Male bee reproductive organs include mucus glands, seminal vesicles, testes, ejaculatory duct, vas deferentia, and an endophallus. During the late pupal stage, a drone’s testes are already fully developed and produce spermatozoa.

When the spermatozoa are housed in the seminal vesicles after traveling from the testes through the vas deferentia, which happens toward early adulthood, the bee’s testes shrink and become rudimentary. Before ejaculation, the bee’s two mucus glands empty into the ejaculatory duct and mix with spermatozoa.

A multi-component system called the endophallus consists of two membranous pouches (horns or cornua), two chitinous plates, a bulb, and a hairy patch and takes up a large area in the bee’s abdomen. It will remain deeply invaginated until copulation takes place. After the drone has mated with the queen, its endophallus turns inside out.

Conclusion

Bees are interesting and complex insects, and it is fascinating to learn how they operate to provide something we all know and love; honey! We hope this article has helped you better understand the bee and made you aware of how wonderful these little creatures are.

References